The Rolls-Royce logo, the Spirit of Ecstasy

[ad_1]

Lord Montagu of Beaulieu was one of Britain’s motoring pioneers. As founder and editor of The Car Illustrated magazine, he employed an illustrator, Charles Sykes, and a private secretary, Eleanor Velasco Thornton.

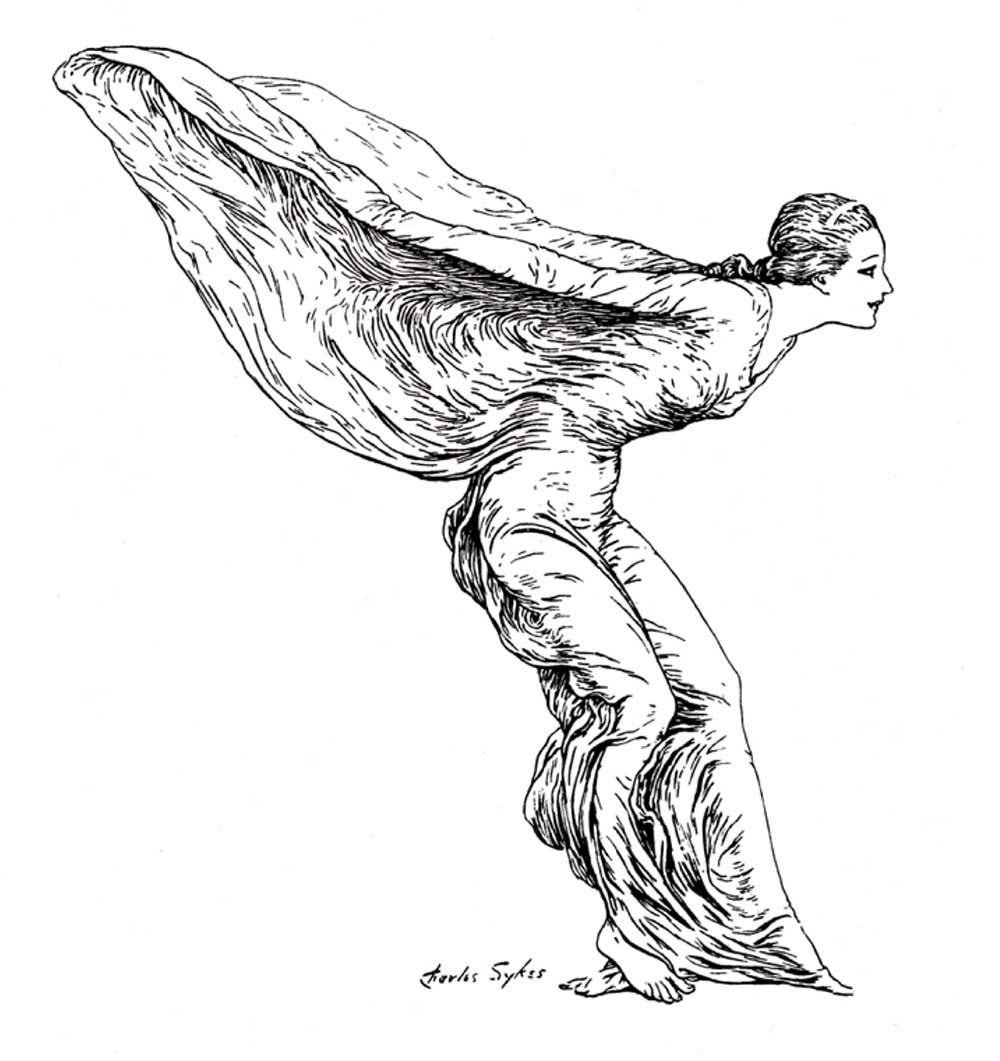

In 1909, Lord Montagu commissioned Sykes (who was also a sculptor) to make a mascot for his Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost. Sykes produced a statue of a young woman in fluttering robes, which he named “The Whisper.” The figure is holding a finger to her lips, which some claim is a reference to Lord Montagu’s close relationship with Eleanor. Others suggest, more prosaically, that it relates to the engine’s quietness.

Whatever the truth, The Whisper went on to adorn every Montagu Rolls-Royce. Soon, other owners were having their own ornaments made, much to the displeasure of Rolls-Royce general managing director Claude Johnson. In 1910, Johnson commissioned Sykes to make an official mascot to protect the company’s products from these unsightly additions. Sykes subtly reinterpreted The Whisper, and created what become known as the Spirit of Ecstasy.

Challenging the social conventions of the time, her appearance became instantly iconic, leaning into the wind, arms outstretched, her dress billowing as if in flight.

Charles Sykes made the mascots from February 1911, until his daughter, Jo, took over in 1928. Jo, the only child of Charles and Jessica Sykes, made the mascots from then until 1939, and has written that her mascot production was about seven per week. This suggests that only about forty percent of the Rolls-Royce cars manufactured between 1911 and 1939 were ordered with mascots (an optional extra). We know that the Sykes’ ceased mascot manufacture after 1939 but most pre-WWII Rolls-Royce cars seen today wear mascots. That would mean that perhaps half of the mascots now on these cars are copies, not made by Charles or his daughter.

The most common question asked by Rolls-Royce owners is whether their mascot is original. The answer depends on what’s defined as “original.” Charles Sykes’ master models are obviously original. From these he made copies, usually four. He then used these as masters to make agar jelly moulds from which in turn he cast wax patterns to be used to make castings. He then polished these castings and sold them to Rolls-Royce to be put on cars. Almost everyone would call these last original, even though they are copies of copies of Sykes’ original sculpture.

In recent years the emblem was carefully redrawn by Marina Willer’s team at Pentagram in London.

The static interpretation was combined with Pentagram’s “expression generator,” adding some flexibility, freshness, and distinction to the Rolls-Royce identity.

Today, each Spirit of Ecstasy ornament is cast in Southampton, England, and can be produced in 24-carat gold, sterling silver, glass, stainless steel, and even illuminated. The Black Badge cars feature a black Spirit of Ecstasy, and for security the figurine retracts when the ignition is turned off.

It’s still unclear whether The Whisper or the Spirit of Ecstasy were truly based on Eleanor Thornton. Either way, Eleanor would never see her likeness achieve global fame. In 1915, she was killed when the P&O liner SS Persia, on which she and Lord Montagu were travelling to India, was torpedoed off the coast of Crete by a German U-boat.

Charles Sykes never spoke publicly about Eleanor, while his daughter Jo confined herself to saying, “Eleanor was a lovely person. It is an interesting story, and if it makes you happy, let the myth prevail.”

Sources:

rolls-roycemotorcars.com

rroc.org.au (PDF)

bmwgroup.com

beaulieu.co.uk

wikipedia.org

[ad_2]

Source link